A recent study showed that a pair of googly comic eyes on the front of a self-driving car can reduce traffic accidents.

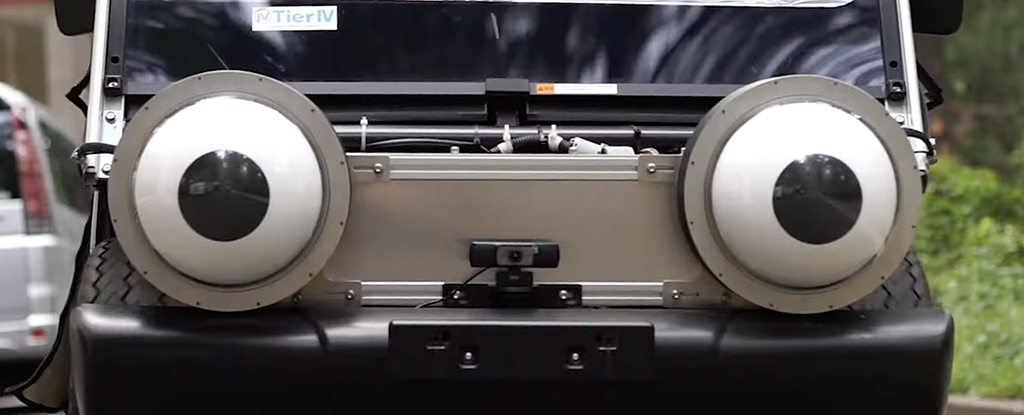

This was proven, when researchers in Japan installed a golf cart with two large remote-controlled robot eyes, which looked like the children’s TV character ‘Brum’.

In virtual reality (VR) experiments, they found pedestrians were able to make ‘safer or more efficient choices’ when eyes were attached than when they were not.

According to the researchers, pedestrians generally like to see vehicle drivers know that they have noticed and are aware of their presence.

But in a future where self-driving cars are commonplace, pedestrians won’t be able to do this because the driver’s seat will be empty.

Therefore, keeping an eye on self-driving cars can help pedestrians assess whether they should not cross the road, and in turn avoid potential traffic accidents.

“There is not enough investigation into the interactions between self-driving cars and people around them, such as pedestrians,” said study author Professor Takeo Igarashi at the University of Tokyo, as quoted by the Daily Mail.

“So, we need more investigation and effort in such interactions to provide safety and reassurance to the public regarding self-driving cars,” he added.

If there is an eye on a self-driving car in the future, the direction of the eye should be synchronized with that self-driving car’s vision system.

In other words, if pedestrians see eyes looking at them, they will know that self-driving technology has ‘seen’ and is aware of their presence.

Self-driving cars often use cameras and ‘LiDAR’ units for sensing to recognize the world around them.

For the study, Professor Igarashi and colleagues wanted to test whether directing one’s gaze at a vehicle would affect risky behavior, in this case, whether people would still cross the road in front of a moving golf cart in a hurry.

The golf cart can’t actually be driven alone, but driven by one of the researchers. The windshield is closed to give the impression that there is no driver inside.

What’s more, the team chose to conduct the experiment in VR, rather than real life, on the basis that it would be dangerous to have volunteers walk in front of a moving vehicle.

In all, 18 participants in Japan, nine women and nine men aged 18-49, experienced four scenarios in the VR experience. Two when the carriage was eye-catching, and two when it wasn’t.

When a vehicle is equipped with robotic eyes, it sees pedestrians and records their presence or moves away and does not record them.

Participants experienced the scenario several times in random order and were given three seconds at a time to decide whether or not to cross the road in front of the golf cart.

The researchers recorded their choices and measured the ‘error rate’ of their decisions so how often they chose to stop when they could and how often they crossed when they should have waited.

Overall, participants were able to make safer or more efficient choices when eyes were attached to golf carts, despite gender differences in the results.

The male participants made many dangerous crossing decisions (such as choosing to cross when the car was not stopping, but these mistakes were mitigated by the train’s stare.

However, there is not much difference in safe situations for men, such as choosing to cross when the car is about to stop.

On the other hand, female participants made more inefficient decisions, such as choosing not to cross when the car was about to stop, but these errors were also reduced by golf cart eye gaze.

However, there was not much difference in unsafe situations for women, such as choosing to cross when the car was not stopping.

“The results showed a clear difference between the sexes, which was very surprising and unexpected,” said study author Chia-Ming Chang.

“While other factors such as age and background may also influence participants’ reactions, we believe this is an important point, as it suggests that different road users may have different behaviors and needs, which will require different means of communication in future independent driving. .”

As for how eyes make participants feel, some even find it funny, while others find it scary or scary.

For many participants, when eyes looked the other way, they reported feeling that the situation was more dangerous, and when eyes looked at them, others said they felt safer.