If it seems like you’re seeing more Teslas on the road, you’re not going crazy. With the promise of reduced carbon footprints and a lower total cost of ownership, the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) has been steadily on the rise. A number of high-profile rollouts are planned for next year, with electric versions of the Chevrolet Silverado and Mercedes-Benz EQE SUV slated to hit sales floors, and as the market matures, consumers are seeing plenty of incentives to purchase EVs.

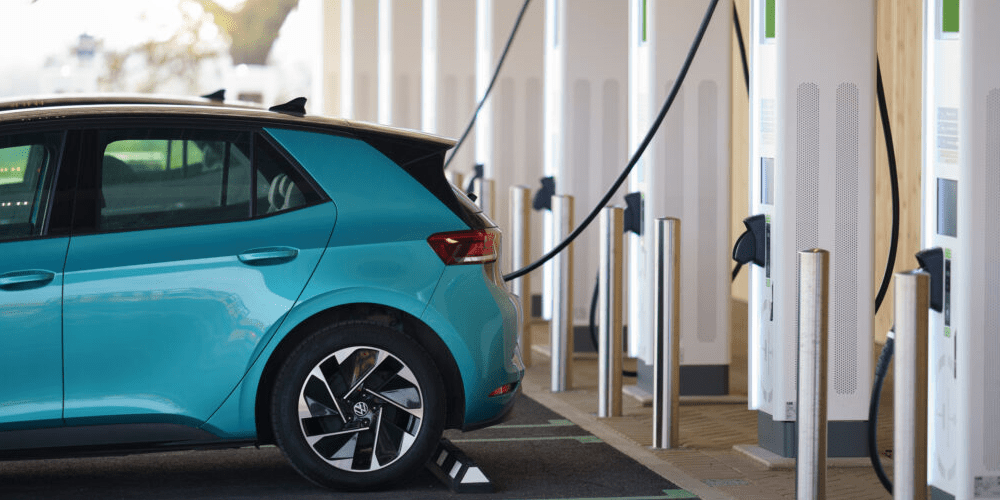

Despite the momentum we’re seeing with EVs, there is a major roadblock standing in the way of widespread adoption: the lack of available charging stations. As it currently stands, the nation’s charging network is simply not accessible enough to make EVs a real, viable alternative to gas-powered cars.

To paint a picture, there were about 1.7 million EVs in the United States in 2022 – a more than four-fold increase since 2018, but still less than 1% of the all vehicles on the road. If the Biden administration is to hit its ambitious goal of EVs making up half of new car sales by 2030, the nation needs a charging infrastructure to ensure that those cars can keep moving. While the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocated $7.5 billion to install 500,000 new electric vehicle chargers by 2030, the placement of those chargers will be critical to how easily Americans can travel with EVs—especially across the country—and remains one of the biggest hurdles to mass adoption.

The EV infrastructure challenge

Currently, 80% to 90% of all EV charging is done at home, but there is a significant need to provide charging for travelers who wish to venture beyond the immediate vicinity of their neighborhoods, and even metro-area dwellers who do not have a residential environment to install individual chargers.

Businesses, manufacturers and local municipalities will have to look for an optimized approach to a charging infrastructure. Within cities, this infrastructure could, for example, take advantage of large parking lots like those at Walmart stores or shopping malls, as well as parking lots outside of apartments and office buildings.

Along highways, however, it can be difficult to determine the exact spacing of charging stations. Considering that the typical EV range is about 250 miles, EV chargers should be placed at intervals that are well within this distance. It’s also important that they be easily accessible to cross-country travelers, and be placed within a mile of highway exits or, in more rural areas, rest areas that do not exceed this distance. While the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) has not formally dictated to states where they should place these chargers, they have recommended that EV chargers be installed every 50 miles along interstate highways.

While these are good guidelines, it’s important to note that the amount of charging stations required in each location can vary geographically. A recent study that looked at the ratio of registered EVs to charging stations found that the states with the best ratios simply house few enough EVs to accommodate them with a small amount of charging stations. For example, North Dakota has a ratio of 3.18 electric cars to one charging station. Meanwhile, California, despite being a hotspot for EVs, ranked as the fourth least-accessible state for EV owners. As the most populous state, it has a ratio of 31.2 EVs to each charging station—proving that the infrastructure just isn’t in place to make widespread EV use a truly workable option. As at-home charging continues to be the prominent charging location, states will need to consider population density as part of the equation in their decisions for charger placement, as it is within these communities where long trips away from home are more likely.

Another consideration while mapping out charging infrastructure is battery life. Predictions estimate EV battery life to triple in the next 20 years, which could change the ideal EV-to-charger ratio. As states think through infrastructure buildouts, they should regularly examine the battery range of current EVs so that they can plan for the future while also ensuring EV chargers are well placed within the range of today’s EV mileage.

What does this mean for consumers now?

The question consumers, including businesses that rely on fleets, are left with is: does it make sense to buy an EV now? While many are incentivized to make their purchases now via state-based tax credits and rebates, and even the Security and Exchange Commission’s pending climate-related reporting rules, that doesn’t necessarily mean that now is the best time to buy.

Because the necessary infrastructure is still being built out, consumers must make important considerations based on their location, available resources, and their driving lifestyle. For example, EVs can be practical for consumers now who live in urban areas with ample access to charging stations, as well as people in rural or suburban areas if those areas have a plan for a charging infrastructure. Lifestyle is another important consideration; EVs can work well for those who will use it for commuting to work or other short trips. If you have long-distance road travel planned in the future, other alternatives would be best until a nation-wide infrastructure is set given the range limitations of current EV batteries. This is exacerbated for those who live in an area with no plans for DC Fast Charging infrastructure expansion, such as Alaska.

Until a robust charging infrastructure is developed, EVs simply cannot be a reality for everyone at this time. Consumers must fully consider charging station availability and their lifestyles before they can wave goodbye to their gas-powered vehicles permanently. However, with continued collaboration between federal agencies, community leaders, and even public-private partnerships, we’ll soon have a nation-wide charging infrastructure that will make EVs a viable option for everyone.